Rebecca West is one of the seemingly limitless number of people who was colossally famous in the 20th century and now seems to be nearly forgotten. As you can see, she was a big enough deal to wind up as the cover story of Time Magazine in 1947. She had a truly remarkable life, living until she was 90. She was a world class journalist, covering the Nuremberg Trials for The New Yorker, a novelist, a Feminist (she's name checked in Virginia Woolf's a Room of One's Own - I mean, does it get any better than that? Chapter Two, if you're interested), political crank, an intellectual who began her adult life as an actress (her real name was Cicely Fairfield, Rebecca West was the stage name she chose, from Ibsen's Rosmersholm) and all around fascinating person.

Rebecca West is one of the seemingly limitless number of people who was colossally famous in the 20th century and now seems to be nearly forgotten. As you can see, she was a big enough deal to wind up as the cover story of Time Magazine in 1947. She had a truly remarkable life, living until she was 90. She was a world class journalist, covering the Nuremberg Trials for The New Yorker, a novelist, a Feminist (she's name checked in Virginia Woolf's a Room of One's Own - I mean, does it get any better than that? Chapter Two, if you're interested), political crank, an intellectual who began her adult life as an actress (her real name was Cicely Fairfield, Rebecca West was the stage name she chose, from Ibsen's Rosmersholm) and all around fascinating person.Her personal life was equally interesting and varied. She had a decade long affair with the much older H.G. Wells and had a son with him while Wells was still married to somebody else. She feuded with her son their whole lives, one of his grievances being she pretended, in his early years, to be his "aunt". I first saw her when she served as one of the aged talking heads in Warren Beatty's John Reed biopic, Reds.

I'll likely revisit West again on this blog as I read my way through her oeuvre, but here I want to talk about her 1957 semi-autobiographical novel, The Fountain Overflows. I first read it a few years ago and I loved it so much I didn't trust myself. What I mean by that is, I loved it to such a degree I knew I was blinded as to its objective literary worth. I remember knowing after I finished the first chapter, that unless she did something very stupid indeed, this was likely to become one of my all-time favorites. Needless to say, she did nothing stupid whatsoever, so one of my favorites it remains.

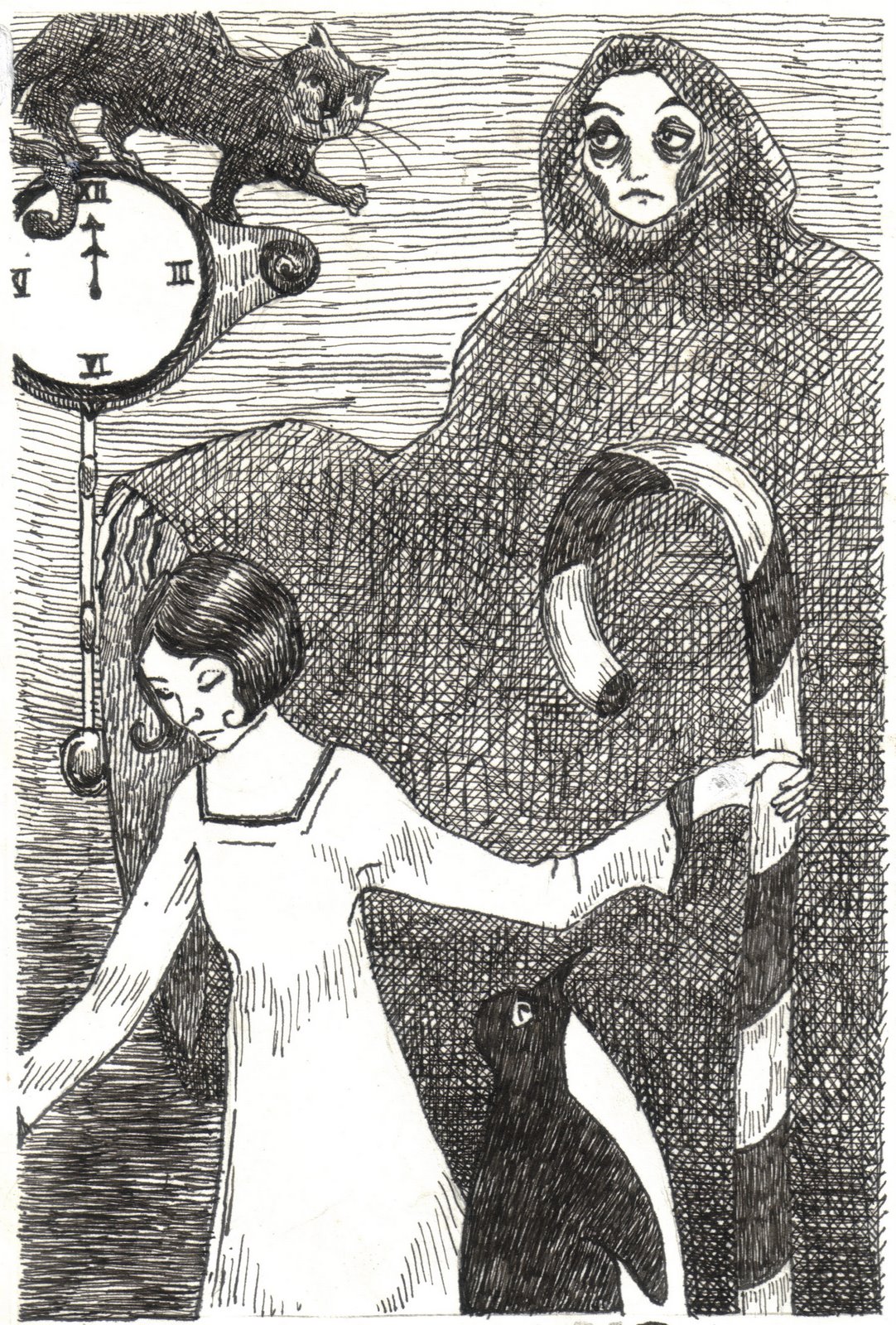

If you ask me what it's about, I'd answer: It's about a musical family (The Aubreys) in the first decade of the 20th century with a father who is a political journalist and a compulsive gambler, a mother who is a former concert pianist, three young daughters (one of whom, Rose, is the narrator) and a young son who is some sort of genius and is little more than a baby when the book begins. It is set in the very first years of the 20th century as the Aubrey family moves from Edinburgh to London, and the girls begin to grow up.

I realize this makes The Fountain Overflows sound like the most conventional novel, but it really isn't. If you ask me again what it's about, I would respond: It's about the difference between children and adults and childhood and adulthood, about art and what makes good art and bad art. It's about poverty and how children respond to it differently from each other. It's about women and how they function in a world in which they have very little autonomy, and about how some optimistically make do and how others flail and nearly drown. It's about what it means if one is a real artist and if one isn't. And how hard it is for each. It's about the uncanny and about how men can sometimes simultaneously knowingly destroy their own lives and unknowingly destroy the lives of those who love them. It might be the funniest and smartest book about what people are like that I've ever read.

The twins, Mary and our narrator Rose, are budding concert pianists. Their elder sister, Cordelia plays the violin, and the great tragedy of the Aubrey family is that Cordelia is a terrible musician and does not know it. This is viewed by Rose and Mary as a far worse tragedy than their poverty or their father's inability to hold onto a job. The worst of it is, though she is a competent musician, she just isn't any good. A distinction that is lost on most people, and Cordelia is a pretty little girl who looks charming when she plays, so she receives heaps of praise. This is simultaneously hilarious and awful and is one of the main threads of the story.

Their father is also both wonderful and monstrous. He's a political journalist of very great repute, who gambles and borrows money, who alienates his followers and friends, who cannot suffer fools. His children are all in awe of him and think him the most wonderful man, but there is a thread of nihilism and self-destruction that also frightens them. Near the beginning of the book, when they are all still small, he gives the children a remarkable and magical Christmas in which they receive elaborate toys he's made himself. They love hearing the stories from his childhood, and they watch as strange men come to the house and demand money from their mother for debts unpaid. There is a remarkable passage in which we find out that public opinion has swung against him, and his friends in Parliament think him mad because of a pamphlet he's written in which all the ills of the 20th century are laid out in black and white. It's full of extraordinary passages as Mr. Aubrey's MP friend shares his dismay and horror with Mrs. Aubrey - who knows nothing about politics but everything about music. She tells him that it's possible her husband is a seer because:

"'I am a musician, you know. We find that in the great composers. Much of Bach and Mozart and Beethoven is much more comprehensible than it was when it was first written, or even than it was when I was young. My teachers found Beethoven's later quartets quite baffling. That can only mean he wrote with a full knowledge of a musical universe that was still chaos while he lived.'"

There is a sequence in which Rose visits her cousin Rosamund and her mother in their shabby house and she and her mother discover them besieged by poltergeists. The ghosts or demons or spirits or whatever they are real and awful. But they are immediately and permanently dispelled once the two little girls and their mothers are finally in the same room as each other. Rose's mother, Clare, calls the supernatural a "dirty business" and is not something to be played with. Everyone in the Aubrey family can prognosticate to some degree or another, but it is not viewed as something that should be indulged, and if one does so the after-effects are never good.

Among all the remarkable set pieces in the book is a good old fashioned, Victorian murder. A school friend of the girls' mother poisons her husband and the Aubrey family wind up taking in the little girl and her aunt. The murderess's family are rich, uneducated Cockneys (while the Aubrey's are, of course, painfully over-educated upper class paupers), and West's descriptions of Aunt Lily are very funny. But what's remarkable is that while they are funny, they are neither condescending or sentimental. West manages throughout the book a combination of uncompromising truth telling and extreme kindness that I've never really encountered before. She's never, ever cruel to her characters, though many do awful things or behave badly.

It's really the oddest book. In some ways it's like the books one reads when one is a child, about a family of (mostly) girls, growing up in genteel poverty, who want to be brilliant musicians. I mean, I know that when one describes it, it sounds like a Noel Streatfeild book. And in a surface way it is like that, and I think if I had read it when I was eleven I would have loved it, too, and it's likely one of the reasons for my loving it (and I use that word literally - the things or people I love more than this book I can count on one hand). But as is so often the case when one reads very well at a young age, one misses nearly everything, and I would have loved it without understanding it - which in some ways is so much of what the book is about, as it is as much about being a girl as it is about anything. It has the shape in some ways of a very traditional sort of book written for young people. But, at its core, its a modernist masterpiece with all the pleasures of Victorian fiction. It's not a book for children, but it's very much about what it's like to be a child, and the child narrator is one of the most extraordinary voices I've read. West manages to make her sound the way children feel in their heads, rather than how they are heard by adults. It's often unclear how much time has gone by or how old the children are, it all flows seamlessly without the traditional markers used in more conventional fiction.

Also unconventional is that the book is entirely about the Aubrey family and their home. There are very few scenes which take place at school. There is no romance of a traditional sort in the book. The more I think about it, the more I think The Fountain Overflows might be an extraordinarily complicated, 400 page character study of Clare Aubrey, the girls' mother. Again, in some ways she resembles that perfect mother of our dreams, Marmee from Little Women. He love is what keeps their family from falling into irreparable chaos and misery, and her love and kindness is on offer to pretty much everybody who enters her home, or is swept up in her wake - including a discarded mistress of Mr. Aubrey's and the mistress's husband (meeting whom, causes her to reread Madame Bovary, which makes her forget to be angry at her husband). We see her through her children's eyes and they are fiercely protective of her, as they think they are tougher then she is, as their childhood was far more difficult, but like children reading a grownup novel - they miss the point a bit.

There is a thread of politics that runs through the book, but West is wise enough, or perhaps I only think she is wise as she thinks as I do, that people are more important than politics. And this is book that is about people and about art and about family. Rebecca West writes as well as anybody I've ever read, and better than nearly everyone. Her prose is so clear, so sane and so sharp. Her sentences and paragraphs are long, and like the novel itself, perfectly constructed. As she writes about the Aubrey family and their friends it's as if she's wielding a sharp paring knife, cutting deeper and deeper into the truth of who these people are. Her criticism could be vicious when she was young. Shaw said of her: "Rebecca West could handle a pen as brilliantly as ever I could and much more savagely." And here she cuts very deeply indeed, but never thoughtlessly, never unkindly.

In her author's note at the end of the book West writes:

"The main theme of the book might be said to be the way human beings look at each other inquisitively, trying to make out what is inside the opaque human frame. Piers and Clare Aubrey loved each other but never really knew how the other one thought and felt. Mary and Rose were divided from Cordelia and watched each other in irritated misapprehension, and were divided from Richard Quinn and looked at him in hope of comprehension. They were all looking for clues to understanding... But I only wrote this book, which is not to say that I am the best authority on what it means."Whatever it means, I can say I love the Aubrey family and maybe that's enough meaning, really. West wrote two sequels, This Real Night and Cousin Rosamund, both still unfinished at her death in 1983. She apparently spent years tinkering with them and never thought them ready for publication. However, they have both been published posthumously, and they both sit on my shelf waiting to be read.

2 comments:

I hope by now that you've found time to read at least the second novel in this series. I, like you, didn't trust my sense of the first novel, but really loved it. So much so that I immediately dove into the second and am nearly finished. It is, perhaps, not nearly as polished as the first, but is - in its continuity of story-telling - wonderful in the illumination of characters who first appeared in the previous novel. There is so much here to love: West's wit, insight, flights of fancy, and incredible penetration into a scene and what makes relationships so memorable. I sincerely hope you find your way back to this wonderful author. What makes her so special? It's the meandering narrative, the incredibly long and involved paragraphs, and the fading between chapters - invisible fading, as though one is arriving into the scenes from the wallpaper, and leaving by the baseboards. It's so different from what is being written today, with no sense of 'framing for cinema." Perhaps that's why, more than fifty years later, this wonderful author has never had a film created (to my knowledge) of these semi-autobiographical works.

It's like finding literature again.

Thanks for your wonderful review.

Go for the second novel. If you loved the first, so much of what you wonder about will start to unfold.

Post a Comment